Creating codes for indoor wireless

Public-safety agencies face poor indoor radio coverage, especially at 800 MHz. Poor coverage is caused by both building losses and by interference from intentional and unintentional emitters. Many such agencies believe it is fair and reasonable to make the building owner responsible for assuring a viable public-safety radio signal throughout his or her property.

This is particularly true when the development itself greatly attenuates the public-safety radio signal or activities at the development increase the need for public-safety response to the site. The alternative is to place the burden of adequate radio coverage on the community as a whole or to settle for situations where public-safety communication is not reliable.

Though many fire chiefs place indoor radio coverage in the same category as the need for adequate fire escapes or sprinkler heads, first responder radio coverage today is not explicitly addressed in national fire codes, such as the National Electric Code, so there is no nationwide standard to use as a guide. Some municipalities have written building or fire codes to address this problem, but results often are poor because the code is not written in a language that is measurable or enforceable.

Measuring indoor radio signals involves an understanding of the complex propagation environment, the application of sophisticated measurement techniques and the use of statistics for data analysis. These techniques and methods are just now attracting the attention of industry standards committees, and their use is not yet widespread for indoor applications.

To be effective, an indoor wireless fire code should answer the following questions:

-

What types of buildings must have such systems?

-

Who is responsible for specifying, installing and testing the original system?

-

Who maintains the system after it is installed?

-

What methods are used to measure radio coverage?

-

What enforcement mechanism is used to ensure it gets done?

-

How is performance periodically verified?

-

Are remote monitoring and alarming required?

Except for coverage testing (where science reigns), there are no universal answers to these questions. Thus, it is likely that every code will be somewhat different. As radio engineers and technicians, our main concern is that uniform and effective methods are used for measurement. That will be the main focus of this article, but we also will try to address — at least partially — some of the fuzzier issues.

Most codes grandfather existing buildings, which is little comfort to the fire chief, but it is politically expedient. Rarely do such codes apply to all buildings, and there usually is a lower limit on building size, say 25,000 square feet, though exceptions may occur for special cases such as nursing homes and schools. The building owner or developer is required to comply with the code before a certificate of occupancy is issued. Ideally, the fire department or other qualified department in the city verifies that coverage exists, either through direct measurement or review of the owner’s test results.

The building owner typically is not a radio expert, and the architect rarely has a radio engineer on his or her team. Thus, uneven quality should be expected unless the code is very specific regarding distributed antenna system (DAS) type or the city approves all plans before construction. After construction, technical expertise on the part of the owner is even less likely, so the fire department may choose to take control of the indoor system following successful acceptance tests.

No system is 100% reliable, so periodic inspection and testing of the system is required. A visual inspection of the system ensures it is powered up and there are no hardware failures. Alternatively, a good remote monitoring and alarm system furnishes the same information.

Testing often encompasses just a functional test of radio coverage and may be as simple as performing push-to-talk calls at several locations in the building. Testing reveals problems that may not be discovered by a visual inspection or by remote monitoring. All systems must have backup power, either a generator or an uninterruptible power supply, or both. A modern DAS should include a remote monitoring and alarm capability so equipment failures are identified promptly.

Next, let’s discuss testing methods. The suggested measurement techniques that follow are based in part on TIA-TSB-88B.

After installation, the system must undergo an acceptance test to prove it meets the coverage requirement. Many of the same techniques used in drive testing should be used for indoor measurements. We know the signal is subject to multipath fading, so we want to compute a linear average taken over at least 40 wavelengths and using at least 50 subsamples (MRT, April, page 42).

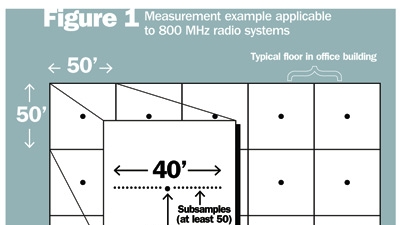

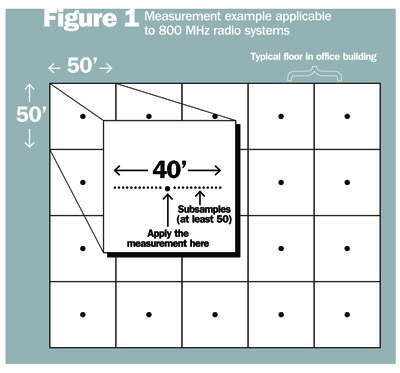

Measurement locations should be uniformly distributed to the extent practical. A practical approach for 800 MHz systems is to place an imaginary grid with 50-foot centers over each floor of the building, as shown in Figure 1. The test receiver collects continuous measurements of the test signal (e.g., control channel) as the engineer or technician walks a distance of 40 feet (about 40 wavelengths). The measurement is applied at the center of the grid square. The survey continues until all grid squares are measured.

Like outdoor systems, indoor systems are subject to radio frequency (RF) interference. The true measure of performance is the carrier-to-interference plus noise ratio, or C/(I+N), not simply the signal level. Unless interference can be ruled out, it is necessary to also collect interference measurements and to compute the C/(I+N). Typical 800 MHz interference sources inside buildings include cellular DAS, 900 MHz unlicensed radio systems and Wi-Fi access points. If the interference is broadband, one effective approach is to measure signal power on an idle channel and assume that interference power is the same on all channels. A typical service threshold for C/(I+N) is 20 dB.

The service area reliability (SAR) normally is computed as the ratio of the number of grid points exceeding the service threshold to the total number of grid points measured.

At this point, we should address a couple of problem areas that apply to indoor systems but not necessarily to outdoor systems. First, the number of grid points will be much smaller than for outdoor surveys, even for large buildings. Consequently, statistical verity is more difficult to achieve when computing the SAR and the confidence intervals. Generally, outdoor systems are specified for a SAR less than 100%-95% is typical because 95% of the cost of the system goes to achieving coverage in the last 5% of the coverage area, and no one can afford a system with 100% coverage over an entire city.

However, indoor systems are different in this regard. In a multi-story office building, we already know where the 5% area of no coverage will be — the basement. The building owner can achieve 95% coverage without any amplifier system simply by including all of the above-ground floors in the survey. But the original problem remains. For indoor systems, then, it is not unreasonable to specify 100% coverage as long as there are specific instructions concerning the areas that must be measured and how they are to be measured.

If a DAS is needed to correct coverage problems, how involved should the public-safety agency be in the selection and installation of the system? Most DAS amplifiers are wideband, so there is some danger that an improperly or inadequately filtered system will pass other radio signals and create harmful interference on either the uplink or the downlink. For example, uplink signals originating from rooftop donor antennas will see multiple public-safety repeater sites and cellular radio cell sites, potentially causing harmful uplink interference. For this reason, it might be prudent to certify the end-to-end system and not just the indoor coverage. At the very least, the public-safety agency should have a record of all bidirectional amplifier or DAS units in the city, so interference problems can be investigated efficiently.

Jay Jacobsmeyer is president of Pericle Communications Co., a consulting engineering firm located in Colorado Springs, Colo. He holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Electrical Engineering from Virginia Tech and Cornell University, respectively, and has more than 25 years experience as a radio frequency engineer.

Acknowledgement:

Ron Whitehead, formerly deputy chief of the Bloomington (Minn.) Police Department, contributed many of the concepts discussed in this article.