All for one, one for all

Whenever we think of emergency response, our thinking often is limited because we focus on what we do in the normal course of our duties. Often, the role each responder plays is well defined by the type of response that is required. Each has specific duties and those duties often are well detailed by both perception and training. But what about those roles when the situation isn’t as well defined? How well do we respond when the situation changes?

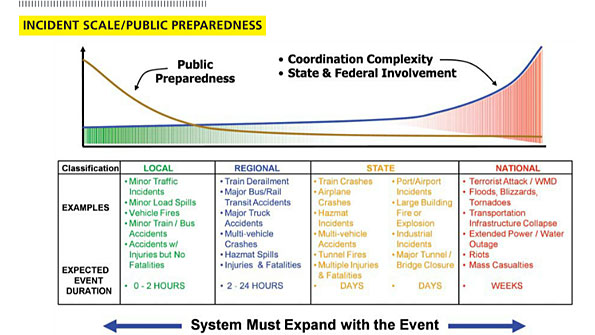

In 2007, John Contestabile, while with the Maryland State Highway Administration and serving as vice chairman of the American Association of Highway and Transportation’s Special Committee on Transportation Security and Emergency Management, created a graphic that expressed the relationship between the scale of an incident and the public’s preparedness. (See graphic above.) Simply put, the more widespread or complex the incident is, the less prepared the public is to deal with it and, hence, the greater the need for state and federal assistance. The graphic also indicates the type and length of response needed to mitigate various emergency incidents.

Reading from left to right we can see that local events such as minor traffic tie-ups or fires are handled quickly and efficiently. The public experiences minor disruptions, but after an hour or two the problems are cleared. Both emergency responders and the public are well-prepared to handle such incidents, with little thought given to alternatives or the impact of the event on daily lives.

However, we also can see how a minor incident can escalate into one that affects not only the immediate area, but also a larger region. We’ve all seen where a crash on a major commuting route quickly begins to impact traffic during peak periods. Traffic begins to backup as lanes are closed to provide space for the responders to treat the injured and begin clearance activities. Traffic backups due to lane closures create additional problems as secondary accidents begin to occur within the queue that require even more response, lane closures and delays. The areas surrounding the initial incident also are impacted as people seek alternate routes; residential streets begin to see increased amounts of traffic, with an increased likelihood of additional accidents as drivers unfamiliar with the area travel through.

The demands on both emergency responders and planners increase as we move toward the right side of the scale. What could have been handled entirely by the initial on-scene personnel now has grown into an event where other disciplines now must become involved. Personnel have to be brought to the scene to evaluate any secondary damage to the road or environment. Public information officers may be needed to handle the media and provide official information regarding the incident and the response. Utilities may be required to secure power or gas lines in the area. Heavy equipment may be required to both stabilize and remove debris. What had started as a relatively minor incident quickly escalated to something affecting an entire region.

Recently, one state transportation agency conducted a tabletop exercise that began as a very minor traffic incident. A vehicle stopped alongside the highway outside a major city with a flat tire. When a highway-safety truck stopped to offer assistance in changing the tire, the driver noticed that something didn’t seem quite right. The back of the vehicle had been modified and a number of barrels and wires could be seen. The vehicle’s driver at first refused assistance and then asked to be transported away from the area. State police were contacted along with a hazardous-materials team. The vehicle was found to be carrying both chemicals and radiological materials. You can begin to fill in the details on how this minor incident quickly became a major incident involving responders from every level of local, state and federal agencies.

The after-action review of the exercise identified the need for better communication and information flow between agencies, which tended to closely guard key data, even though it wasn’t important to their response. Agencies that should have made information available about the amount and types of hazardous materials didn’t. This affected the emergency response planning, as the size of the affected area was unknown. Without an understanding of the affected area, closures and evacuations couldn’t be planned. Information that was given to the public was fragmented and incomplete because details were not being shared by the responding agencies; this led to panic as the media largely resorted to reporting speculation and rumors. Another key point uncovered in the review was a lack of a clear command hierarchy. Even though the Incident Command System was supposed to be in use, agencies often refused to follow protocol rather than cede command to more qualified personnel.

In addition, planning gaps were uncovered regarding the identification of available assets and the determination of what actually was deployed. Alternate routes around the exclusion zone were unable to be identified because key data was not being shared. Medical facilities had no information regarding the number or type of injuries; consequently, they could not determine the level of assistance they would be called upon to provide. While one strategy was to have public shelters in place, no thought had been given to forced evacuations or how to transport people. Emergency planners had assumed sufficient busses would be available, without knowing the number or type available. Gathering points had not been predetermined nor had shelters been set up.

Command and control for the incident quickly deteriorated due to a lack of common communications facilities. Without the means to communicate quickly and securely, assets were wasted as incident commanders could not get a clear picture of the situation at different posts. Disparate communications systems also contributed to information not being shared as needed. This led to decisions that were based on an incomplete understanding of the situation and their local policies of what information was to be shared.

Several months after the exercise, leaders from some of the agencies that were involved met and discussed the lessons that were learned. While it was agreed communications was the major issue, one agency head, when asked if they would do anything differently reportedly responded, “Probably not.”

The majority of us will never be involved in an incident of the magnitude from this tabletop but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t plan for such an event. There are four phases to any emergency: the planning, the preparation, the response and the recovery

Most of us are very good at the response part but are not involved in the other three. Every agency needs to be more involved in all phases — and that means opening the process to where we look outside our own agencies.

William Brownlow is AASHTO's telecommunications manager.