The best time to measure RF interference

The best time to measure RF interference

External interference can be devastating to radio communications systems. No matter how well designed a system may be, on-channel interference can degrade or inhibit communications. Searching for interference can be extremely painful and time consuming, and the communication system often is unusable during this time. Sometimes, the problem is not easily mitigated, even after the source of the interference is identified.

So, what is the best method for preventing interference from adversely affecting a system? The answer is to measure the RF environment at a location before a system is installed.

External interference comes in two different forms — signal and noise. Signal interference occurs when some active transmitting device affects your system. These signals can be transmitted on the same frequency as your system (co-channel interference), on an adjacent channel (adjacent-channel interference), or on a nearby frequency, often resulting in a diminishing of the radio’s sensitivity (receive degradation). Interference from nearby strong signals (when frequency separation is sufficient) usually can be resolved with a combination of filtering on the signal source (to remove transmitter noise) or on your system (to prevent receive desensitization).

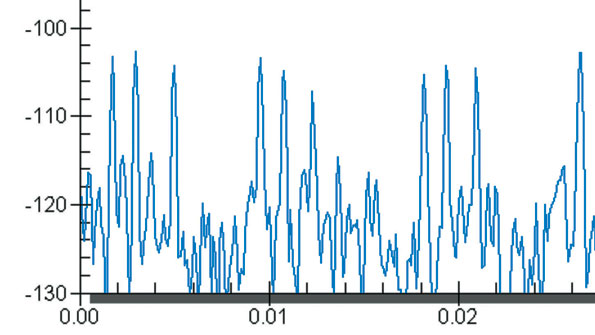

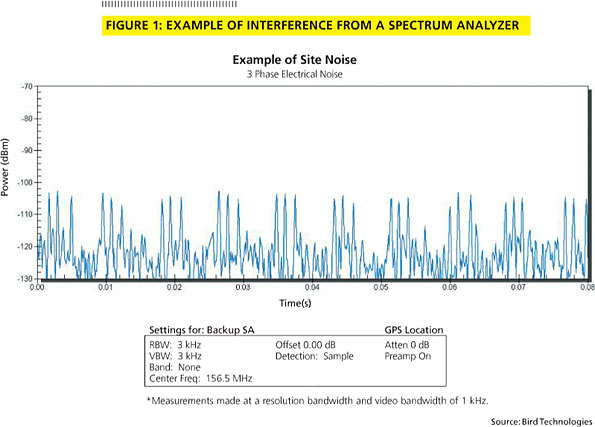

Environmental noise results from broadband RF energy created by anything and everything in the nearby environment — for instance, computers, power lines, and even the sun. By its nature, noise always will be on-channel and cannot be filtered out at the receiver. This means that there are three options when dealing with noise interference: find the source and fix the problem; move the site or change the frequencies being used; or live with the noise interference.

Some amount of noise will be present at any location. Even at a location free of any man-made noise, the vibration of atoms causes a minimum amount of noise. This is called the “thermal noise floor.” However, the real world is hardly ideal, and noise levels greater than 20 dB above this thermal noise floor can be observed.

Usually, this environmental noise stems from a large number of small sources, making mitigation impossible. But, even in the rare case where noise is coming from a single source, finding that source can be a tough prospect. Any electronic device with current can be a source of noise. Generally speaking, the higher the electrical current, the more likely a device is to create noise. For example, transformers and power lines often emit noise when malfunctioning, particularly on lower frequency bands such as VHF or shortwave.

In these cases, a decision has to be made whether the degradation of sensitivity caused by the noise can be tolerated. If not, then a major change in the infrastructure is warranted, such as altering individual frequencies, moving to a band less susceptible to noise, or even moving the location of the base-station infrastructure. None of these options would be considered an easy fix, which is why identifying this noise before installation is crucial.