A different kind of hacking

Upon the mention of “network security,” many communications administrators first think of hackers, viruses and other software attacks that can compromise the integrity of information transmitted over the network. Ensuring that network hardware remains intact also is a priority, which has spawned an industry focused on fencing and secured facilities to house valuable base-station equipment.

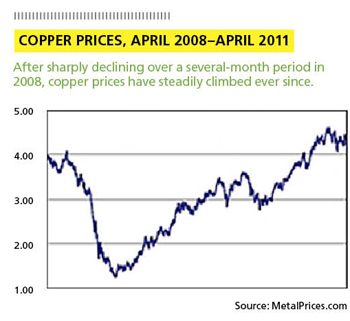

But the sizable investment made in securing the network can be rendered useless quickly by criminals extricating copper grounding and/or wiring, something that has become a growing problem in the communications sector and other industries as the price of copper has skyrocketed during the past decade. Copper is a hot commodity on the open market.

“With the price of copper hovering over $4 per pound and a lot of trades people out of work that have tools and skill sets necessary to harvest this material, it’s created a very active area of theft,” said David Meurer, president of Armed Response Team, an Albuquerque, N.M.–based vendor that has developed a solution designed to combat copper theft at enterprise locations. “I cannot understate the broad nature of this problem. … It’s everywhere, and it happens daily — it is widespread.”

For the criminal, stealing copper can generate hundreds of dollars in revenue for a few hours of work. However, the amount of money needed to repair the damage done — in terms of securing replacement parts and payment of crews to do the repair work — often costs tens of thousands of dollars, sometimes more.

And the real cost to enterprises can be even greater. Depending on which copper is removed, buildings can left without heat, air conditioning or electricity, creating subpar working environments or the need to shut down operations until the matter is rectified.

Other copper thefts can threaten safety, particularly when copper is stolen from mission-critical communication systems. In 2008, residents of Jackson, Miss., were not warned of approaching tornadoes in April 2008, because thieves had stripped the copper wiring from area tornado sirens, rendering them inoperable.

“The crook gets off with a few hundred dollars of salvageable materials, but the damage done is always significant multiples of that,” Meurer said.

Initially, the surge of copper theft began about in the mid-2000s, as the price of copper — fueled in large part by construction in growing countries like China — climbed from less than $1 per pound to more than $4 per pound. In 2007, the U.S. Department of Energy characterized copper theft as a $1 billion problem; the following year, the FBI released a report that described copper theft as an “epidemic” in some areas of the country.

David Reeves, vice president of P&R Communications, said that his company experienced its first copper theft in the Dayton, Ohio, area a couple of years ago at a land mobile radio site, and the cost to his business was substantial. It took more than two days for his company to make the necessary repairs.

“They basically steal every bit of copper that’s exposed — they just cut it with a pair of pliers … or bolt cutters,” he said “They probably got $40 to $50 worth of copper, and it cost me probably $2,000 to $3,000 in labor to put it back. It made me want to hang $20 bills on the fence and say, ‘If you’re thinking about stealing our copper, take a $20 and get the hell out.’”

Upon doing some research, Reeves learned that the site — shared by Sprint Nextel and a couple of broadcast radio stations — was not the only one victimized by copper thieves. Instead, he learned that “virtually every site that we checked on the north side of Dayton had been hit” by copper theft.

“Communications systems are very, very vulnerable, because those sites typically are not in easily noticed locations,” Meurer said. “It’s not like it faces a major highway or thoroughfare, where people know what’s happening. They tend to be in places that are somewhat secluded. … It’s the perfect site for these intruders to go in and do their work undetected.”

Wireless communications sites are not the only targets, according to the FBI report. Transformers contain about 50 pounds of copper, making electric-utility facilities attractive to crooks. Copper has been stolen from telephone poles. Construction sites or foreclosed properties can be particularly vulnerable, as wiring is often exposed and HVAC units containing significant amounts of copper may be unprotected.

“This has not been a problem until fairly recently, so buildings were not designed with this problem in mind,” said Craig Dever, vice president of sales for Inovonics, a wireless security vendor based in Louisville, Colo.

For criminals, copper theft can generate a substantial source of revenue for a relatively small amount of time and effort. But it is not without risks — particularly when perpetrators attempt to steal copper from installed sites. Getting caught by law-enforcement is the least of the worries.

“It’s a dangerous way to make a living,” Dever said.

For instance, string of copper thefts at LMR sites in central Florida occurred during an extended period until one of the perpetrators apparently met his demise attempting a heist, said Ben Holycross, radio systems manager for Polk County, Fla.

“With a little ax, they managed to cut into a 440-volt AC circuit. He was deader than a doornail,” Holycross said. “That all came pretty much to a stop, so we think they were responsible for a just a boatload of copper thefts.”

Combating copper theft has proved to be a challenge. Fencing can be a deterrent, but it “doesn’t deter the determined, and some of these people are determined to get that material,” Dever said

Reeves said that his company has been buying off-color copper parts in an effort to confuse less-sophisticated criminals.

“If they see it, and it doesn’t look like copper, they don’t steal it,” Reeves said.

More importantly, P&R has worked with local law-enforcement officials to establish a program in conjunction with metal-recycling centers in Dayton to identify stolen copper parts, which can be identified “pretty easily” if they are un-tampered after being stolen, Reeves said. Video surveillance also is used at some sites. The efforts have had positive results, he said.

But more sophisticated copper-theft rings burn the metal material into forms that leave it indistinguishable from common scrap metal, Meurer said. In addition, arresting a copper thief after an incident does not undo the damage done to an enterprise — the parts still need to be replaced at considerable expense and/or system downtime.

With this in mind, Armed Response Team has developed a sensor-based solution that links to an alarm system via an Inovonics’ radio system that operates in the unlicensed 900 MHz band.

“If somebody comes up and tries to tamper with the door on the enclosure, we want that signal to be transmitted to the alarm signal, then sound a siren and flash a light — let the perpetrator know that their activity has been noticed,” Meurer said, adding that private security dispatchers are alerted simultaneously and take appropriate responsive actions.

Meurer said that the cost of the system typically is between $1,000 and $4,000. A monthly service fee also could be necessary; however, if the enterprise already has a contract with a security firm, the anti-copper-theft solution can be added as an additional zone to that system with no additional recurring cost, he said.

“It is a little bit of investment, but compared to the loss that they face the first time, it’s still modest,” Meurer said. “When compared to the subsequent losses that they would face, it’s just a drop in the bucket. And I’m just talking about the hard-dollar costs; there are soft-dollar costs that are far in excess of that.”