MWC party goes on amid the rubble of telecom

MWC23 – The tail end of Mobile World Congress (MWC) week is always a time of reflection about the show and the state of the industry as bleary-eyed and hungover execs return home, in no shape for anything more cognitive than riffling through reams of restaurant receipts. There are a few things to say about the 2023 edition, but the broad industry themes are ones of desperation and denial as the show rebounds from its COVID slump. MWC is in rude health. The sector itself looks anything but vigorous.

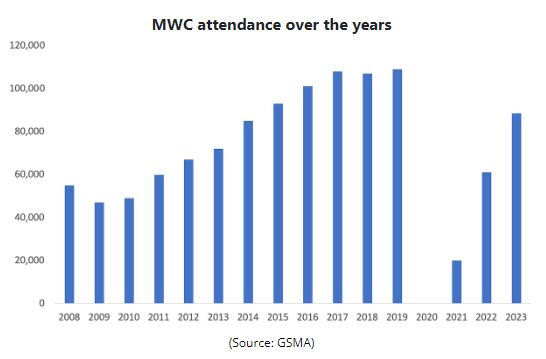

The rivers of people that flowed daily between MWC’s oversized stands proved the industry that figured out how to communicate in real time over long distances has not lost its appetite for congregating in one spot. The GSM Association (GSMA), a lobby group that counts on MWC and related shows for its revenues, estimates there were more than 88,500 visitors this year. And while there is some attendee skepticism that numbers were quite so high, the show felt busier than last year’s, when the GSMA’s estimate was 61,000. A year earlier, during the pandemic, an emaciated MWC attracted as few as 20,000 people, and only 5,000 of them came from outside Spain.

How long this can last while the industry grapples for survival is anyone’s guess. According to a PwC survey cited by Orange CEO Christel Heydemann in Barcelona, 46% of telecom CEOs don’t expect their companies to be around in a decade. Extrapolate the trend and the GSMA will still be hosting its MWC party of thousands amid the corpses and rubble – might as well enjoy yourself when the end of the world is nigh.

Grappling for survival? Isn’t connectivity more important now than ever? The underlying networks will probably endure, grow and evolve into something even more sophisticated (6G sensing networks, 7G sentient ones). But their owners and business models may be radically different. Cellnex, a private equity-backed “towerco,” has chucked billions at infrastructure takeovers. A few years ago, it had 7,500 towers in Spain. Today, more than 138,000 sprawl across Europe. Such shapeshifting is a kind of market correction in a crowded and moribund sector.

Meanwhile, operators are sharing the electronics that hang off these towers and spending less on equipment. Michael Trabbia, Orange’s chief technology officer, thinks new technologies such as open RAN will make that a lot easier. Howard Watson, his counterpart at the UK’s BT, rules out any 5G-like equipment splurge on 6G, whatever that turns out to be. For kit vendors like Ericsson, which makes about 70% of its revenues from network sales, this is alarming.

Old ideas regurgitated

Unfortunately, telcos have no original answers when asked what might replace dwindling connectivity revenues and even spur growth. Instead of coming up with fresh ideas, Europe’s former state-owned monopolies are courting regional authorities about “fair share,” the specious argument that Big Tech companies should contribute to the cost of networks on which they dump traffic. Richard Windsor of Radio Free Mobile summed it up brilliantly in his blog when he said: “Subsidizing failure is a bad idea.”

Sensible authorities would realize digital infrastructure will not die if they ignore the telcos. A more laissez-faire stance on consolidation, a lowering of spectrum license fees and more support for infrastructure rollout would all help the current owners of networks. But if there is genuine demand for high-speed fixed and mobile networks (still not clear in the case of 5G), and less obstructive regulation, the market will find a way.

To read the complete article, visit Light Reading.