Lynk claims successful test of satellite-to-cell-phone communications, cites potential public-safety valueLynk claims successful test of satellite-to-cell-phone communications, cites potential public-safety value

Virginia-based Lynk today announced successful tests of communications between its low-Earth-orbit (LEO) nanosatellites—acting as a “cell tower in space”—and unmodified, standard cell phones and smartphones, showcasing a potential new option for providing resilient backup links and coverage to remote areas.

“The advent of everywhere, everyone communications direct to your phone is upon us.” Lynk CEO Charles Miller said during an interview with IWCE’s Urgent Communications. “It’s coming to a mobile operator near you.”

Today’s announcement focuses on Lynk’s successful reception of a text message from one of its LEO satellites to a typical mobile phone in the Falkland Islands located well outside the range of any U.S. wireless operator.

“It was sitting on a table [outdoors], and it’s been repeated multiple times since then—holding it, using it in different orientations,” Miller said. “It was a smartphone. We were [using] various flavors of phones.”

While the announced test highlights the downlink connection from a Lynk LEO satellite to a cell phone, Miller said the company also has met the more challenging proposition: enabling the uplink connection from a cell phone with limited power to the Lynk satellite.

“We can close the link, up and down, but we’re just not ready to announce where we are on that yet,” Miller said.

Lynk hopes to serve as a roaming partner to commercial wireless carriers, according to Miller.

“It just fills in all of the [coverage] gaps,” he said.

Demonstrating this capability represents the realization of a vision that Miller had when co-founding Lynk—known as UbiquitiLink until the company changed its name last September—after determining that “conventional wisdom was wrong” about the ability to connect satellites to normal cell phones.

“The overall focus of the company started about five years ago, when we figured out that the fundamental physics allowed you to connect the satellite directly to a standard phone,” Miller said.

Technologically, Lynk could begin offering service by the end of the year, but Miller acknowledged that he does not know how long it will take the company to secure regulatory approvals with governments around the world and complete business arrangements with commercial carriers.

Although the announced test utilized GSM technology, Miller expressed confidence that more

“We’re working on both GSM and LTE. Our technology will work with both—and, in the future, it will work with 5G, as well,” Miller said. “This test was GSM in 2G, but we’re not limited to that. We’re just starting with that.”

Lynk currently is testing its connectivity capability while operating in the 850 MHz and 900 MHz spectrum bands, which are airwaves that are used for wireless communications around the world, Miller said. By operating on spectrum below 1 GHz, Lynk believes its signals will not be impacted negatively by rain in the manner that satellite signals operating at much higher frequencies do.

“We don’t think rain is an issue at UHF, in the 800 MHz and 900 MHz bands,” Miller said. “We don’t have any evidence that rain is an issue. Rain fade is an issue at higher frequencies, but it’s not really in the bands we’re using.”

Miller said that all tests thus far have been conducted outdoors.

“We’re not doing this indoors—not yet,” he said. “We’re proving the core, fundamental technology. Down the road, we’ll … improve the performance of it, where you can do indoors and that type of stuff, but that’s not where we start.

Some of the key use cases that excite Miller most revolve around critical communications, particularly as it relates to the ability support first responders and the citizens they serve, even in remote areas and locations where terrestrial networks have been disabled by a natural or man-made disaster.

“When the network goes down, we will provide instant network backup to emergency responders,” Miller said, noting that the transition to Lynk would not require any manual intervention by the user.

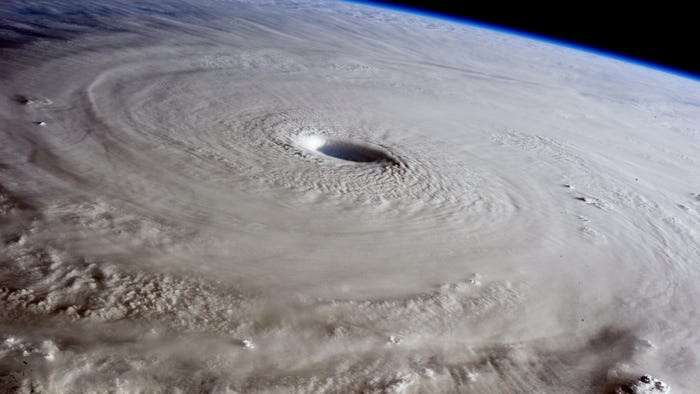

“What happens [today] is that, when the network goes down, it takes days or weeks to get it back up. [With Lynk,] we have instant backup, because when the earthquake or hurricane takes out the ground network, it doesn’t do anything to the space network, and we just work the process out about who gets on the emergency-responder list to get this emergency backup. That’s a service that this technology will provide down the road.”

When asked whether Lynk was pursuing FirstNet certification, Miller indicated that the company does not have a U.S. carrier partner at this time.

“We’re having conversations with all of the U.S. mobile-network operators. FirstNet and AT&T is clearly one of the ones we could go to market with, but that is TBD [to be determined]. Who we go to market with in the United States is an open question.”

In addition, Lynk could help consumers reach 911 in the most difficult circumstances, so first responders know that help is needed, Miller said.

“[Whether they] broke their leg, or they’re out on the ocean or they fall down into a canyon, if people have a phone in their pocket and they’re in really bad trouble, they know exactly where they are—because the GPS in the phone tells them where they are—but they can’t tell anybody [without connectivity],” Miller said. “We solve that problem.

“Now, you can tell somebody where you are [with Lynk]. Over time, there may be apps that automatically send your location as part of you sending a text-based 911. We solve the key problem, which is getting that message to the emergency responders who can save their lives.”

A self-described “serial space entrepreneur” with a background in NASA and nanosatellite launches, Miller said the Lynk concept began as a discussion regarding potential applications that could be supported by nanosatellite technology.

“One of the team members came to me and said, ‘What about the phone?’” Miller said. “I went to one of our technical people and said, ‘Can you connect the phone to a satellite?’ and he said, ‘You can’t do that.’ I asked him, ‘Well, why not?’ And he kind of grumbled, because he knew that meant he had to go do the fundamental physics of the link budget.

“He came back, and the answer was, ‘You have to lower the orbit [of the satellite] to 500 kilometers or lower, and—instead of this big, wide-field antenna—you have a narrow antenna with higher gain and a lower slant range, and you use sub-1 GHz spectrum. If you do those three things, you can close the link from the phone up to the satellite.’ No one had done the work before, in terms of could you do it and how.”

But making the satellite-to-cell-phone link work involved more than simply deploying the software stack normally found in a cellular base station into LEO satellites orbiting about 450 miles above the earth’s surface, according to Miller.

“Under the 3GPP standards, … that technology is not designed for satellites that are moving at orbital velocities, and it’s also not designed to allow connections between the phone and a base station beyond 35 kilometers,” he said.

“So, our key technology IP (intellectual property), which is patented, is how [to] compensate for that at the base station in the sky, so you don’t have to change the phone and can use a standard phone? That is our key technology that we invented three years ago that’s in the satellite, and we’re in the process of proving.”

Lynk has not yet conducted the Falkland Islands connectivity capability in the United State, but the company has received a special temporary authority (STA) license from the FCC to conduct tests demonstrating that the cell-phone-to-satellite communications do not cause harmful interference.

“We have a unique way of doing spectrum sharing that we can light up the spectrum that’s already in the phone in a way that doesn’t interfere with the phone,” Miller said. “That’s one of the innovations that we have invented—how do you use spectrum that’s already in the phone, and broadcast from space to connect to the phone, without causing interference to phone users.”